Let's start way back. Somerset was home to many a distillery centuries ago, but that seems all lost by the end of the 1700’s. Why was that and have you ever come across records or recipes for what was going on back then?

We are inspired by old recipes and writings from the 1600s that talk of an apple distilling industry in Somerset.

Largely, distilling disappeared because of the advent of cheap gin (1700’s) and the industrial revolution. Then the UK had a period of puritanism and taxes which pushed distilling behind closed doors.

Your father came to Burrow Hill in the 70’s and established Somerset Cider Brandy over 30 years ago. What are your earliest memories of the distillery?

I remember the excitement of Josephine - the first still - arriving and the excitement of a decade long campaign coming to fruition.

I can clearly recall the gravitas and respect that the still was held in, the distillery then was a sacred area.

Over the years, is it something that has always had a gravity for you in terms of a family business and was it always going to lead to you, or your siblings, working there?

The apple growing and cider making was very much part of all our lives. You learn by osmosis. The Somerset Cider Brandy Company is something that has evolved during our lifetimes as the industry has become established.

I always worked my holidays in the business and then later worked part time on whatever needed doing. It is such an incredible place to work and live that despite learning other trades my siblings and I are all closely involved in the farm today. I took over as MD in 2016.

Indeed, great family businesses have that gravity for all those involved. You mentioned that you leaned other trades - What were you doing before and is that something that you are still pursuing in parallel?

I studied my masters in The Control of Infectious diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and worked in that for a while (weirdly very transferable skills to running a drinks business), then I worked as a photographer.

The farm is all consuming so I sadly don’t have time to do any photography now although one day I may take it up again.

Getting your HMRC licence was a big milestone for British Distilling, as craft distilling just wasn’t even understood, let alone an industry as it is today. A lot has been said about how stringent it was to begin with but at what point in the journey do you feel attitudes changed towards what you are doing?

When we started there was no craft distilling industry in our area and so we had to learn alongside our local customs. It was all incredibly strict and our architect's plans of the stills include every single nut and bolt and seal catalogued with precision. At that stage we also had to have our warehouse and distillery 3 miles away from where we made the cider and visitors were not encouraged.

There was generally a huge air of mystery and reams of paperwork because nothing was online at that time. Since then HMRC licensing laws have become much more relaxed and there is a lot more information available for distillers so the process of actually running a distillery is much more streamlined.

From a drinker’s perspective – do you think the fact that there are more craft distillers around helps people understand just how special your set up and spirits are, or do you feel you get lumped in with many who just don’t distil from scratch, grow their own produce, have that connection to the land etc?

When we started premium spirits were in their infancy. Then there was an uplift in artisan production which has now been followed by a flood of cheap industrial alcohol being marketed as ‘artisan’ or ‘craft spirit’. This is really sad for the consumer and is especially obvious in the gin industry.

Our hope though is that people are also becoming more discerning and they will appreciate the provenance more. In our case every bottle can be traced back to its source orchard.

That’s some amazing traceability. There’s also a PGI for Somerset Cider Brandy too, which Julian was integral in making happen – how did that come around?

Somerset Cider Brandy was given PGI status in 2011 in Brussels which was a huge moment for the industry and recognises our historical production methods including the type of trees with use and our specific terroir.

Julian fought for it because, due to a clerical error by the UK government, Somerset Cider Brandy was removed from use as a product term (even though it had been used for many centuries). We did not want to lose recognition by having to call our historical product ‘Cider Spirit’.

And what are the rules around it? Do you need specific apple varieties, or is it about the amount of them used, or the kind of orchard (and way that it’s managed), or even the way it’s distilled - Or all of the above?!

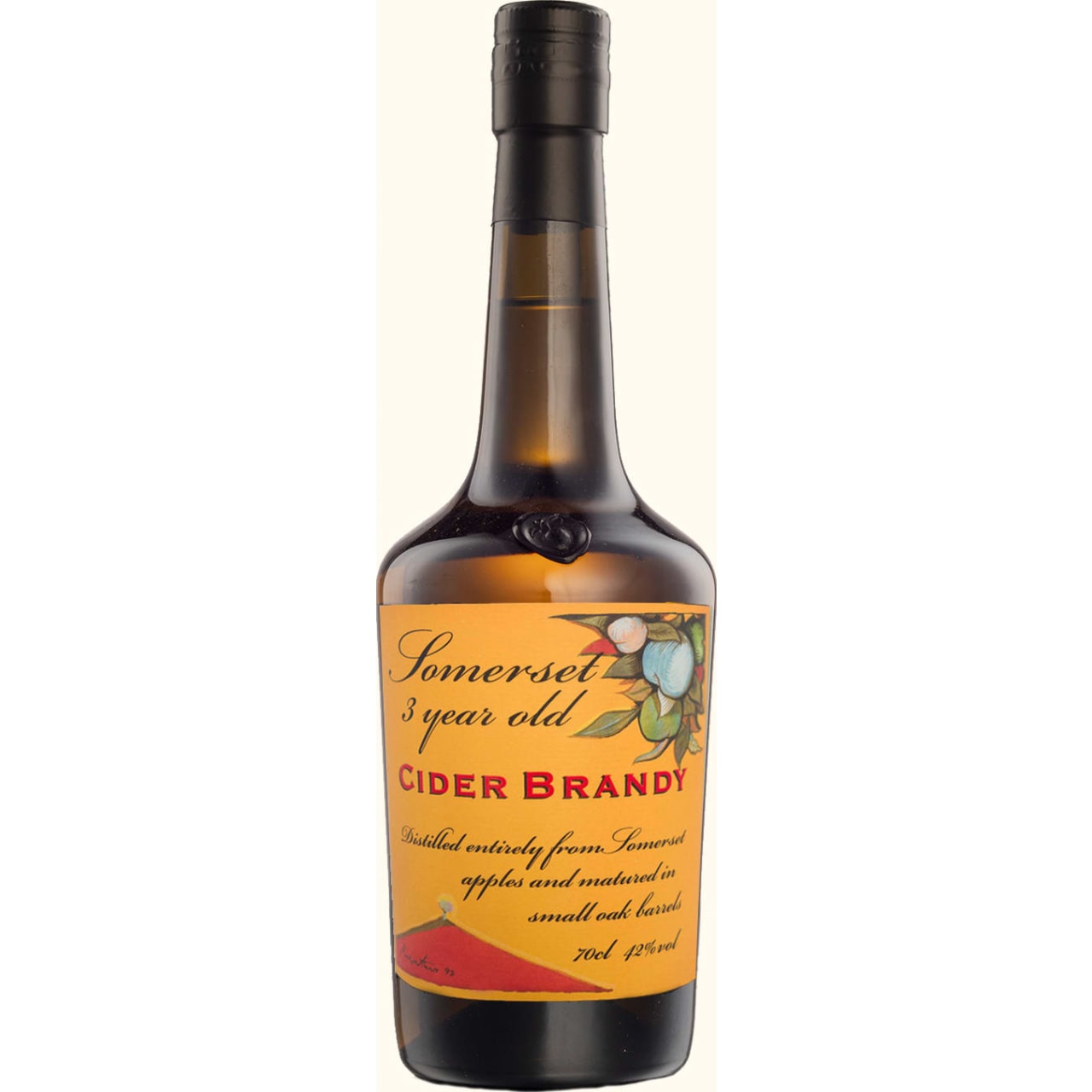

All of the above. A fruit spirit must not be called brandy till it is at least three years in oak barrels. Somerset Cider Brandy must be made of at least 20 traditional heritage cider apple varieties from our specific area of Somerset. Apples must be grown on traditional low yielding standard orchards which do not use artificial nitrogen or pesticides. There must be no addition of anything but apples throughout the process.

There are also plenty of other rules and regulations about the distillation and aging process and all are about maintaining the best quality with no shortcuts. Much like the protection around Scotch Whisky, the PGI provides real quality assurance.

You grow as well as distil, which puts a different perspective on what the spirit represents and the sustainability issues the industry faces. Climate change, pollution, biodiversity density and crop resilience – there’s so much to consider. What are the key challenges facing you?

The challenges are different every year but the climate is always a worry for any farmer.

The harvests naturally vary a huge amount in volume and quality but the changing climate makes the variation less predictable. We have 105 types of traditional cider apple on the farm and our harvest lasts three months. It means that if some early or late varieties fail some of the others may do well. We are also constantly planting to increase biodiversity and aid pollinators, and have small woodland areas between the orchards to encourage this.

Over 100 types of apple that grow on the farm, that’s amazing. What works best for brandy production? Is it a combo of late sharps or late bittersweets or is there a lead variety that does the hard graft?

Distilling cider must be a perfectly balanced cider made purely of apples. In our case we go for 2/3rds bittersweet varieties and 1/3rd sharp apples. This gives it lots of flavour but it also has the acidity needed to keep the cider fresh until distilling takes place.

There are some types of grape, like Folle Blanche or Ungi Blanc that don’t make particularly desirable wine, but make excellent Cognac and Armagnac. Is that the same with Cider Brandy or is it a case of what is good for one is also good for the other?

What is good for one is generally good for the other, although some sharp varieties are far better placed for distilling than drinking.

No sulphites, seasonal variances, fermentation yields – Fruit Brandy is challenging! You can tweak a little through the distilling process itself but in our experience - it’s more of an amplifier than a corrector. In your opinion what’s the hardest part of making great cider brandy?

Good apples and good barrels are the most important factors.

But there are three main components to making a great spirit. The cider, the stills and the barrels. A bad cider will make a bad spirit and only a sensitive distillation will maintain the fruity nature. Then once the eau de vie is made the barrels become the single most important factor for the next 10 to 20 years of the aging process.

There are now three stills running at the distillery. Do each have their various quirks and are they different in terms of the spirit they produce?

Josephine makes a fatter richer spirit and Fifi a fruiter one. Isabel is somewhere in between but is very slow to make spirit. If we are making specifically for eau de vie that will be drunk as eau de vie we will use Fifi. Otherwise, we tend to blend the spirits from the three of them for the aging process as each has its own benefits.

We’re a little bit obsessed with your Somerset Pomona and Kingston Black Aperitif.

Not just because it’s one of the few really high quality Pommeau-style drinks outside of France but also, they are amazing. For those who are yet to discover them - What are they, how do you make them and how would you describe their flavours?

Both are blends of cider brandy and juice that are married together.

The Kingston Black Aperitif just uses Kingston Black apples which are legendary in the West Country. A rare bittersharp apple that we are the main growers of. This is married with Somerset Cider Brandy for 18 months or more.

The Somerset Pomona is more of a digestif. It is also a fortified juice but is a secret blend of apples that’s matured in oak for an average of 2 years. It is slightly stronger and richer. We drink it like you would a port.

Last but not least – best food pairing to enjoy with your 3yr Brandy with?

We often drink this with a cheese board but it is also incredibly versatile in cocktails.